Mark Twain Ate Here. Did Emperor Norton?

Among its "Pacific Coast Items" of 7 December 1878, the Sacramento Daily Record-Union noted grievances first aired in the Virginia (Nev.) Chronicle a week before. The Record-Union reported that "a holder of much Sierra Nevada stock was finding fault with the gastronomical facilities of this mountain town."

The gentleman "was heard to ejaculate:

"'It's about time we had some two-bit restaurant in this town, like the Miners' Restaurant in San Francisco, or the What Cheer House, where a man could get a good, substantial meal without bankrupting himself.'" [emphasis mine]

As we'll learn shortly, the Miners' Restaurant was a regular hangout of Mark Twain, Bret Harte and their journalistic cohort. Was it a haunt of Emperor Norton's, as well?

:: :: ::

The first San Francisco city directory that appeared after Joshua Norton arrived in the city in November 1849 was published 10 months later — in September 1850 — by Charles P. Kimball. Page 84 of the poorly alphabetized Kimball directory lists Joshua at his first business address — an office in James Lick's adobe cottage at the corner Montgomery and Jackson Streets.

The same directory lists — on page 79 — a Miners' Restaurant less than a block away: on Montgomery Street between Washington and Jackson.

So, there's no doubt that Joshua Norton was aware of the place. Did he eat there?

By 1852, the Miners' Restaurant was under new management and had moved to 129 Commercial Street.

Nine years later, the restaurant moved again, to a new location at 531-533 Commercial Street, between Montgomery and Sansome — specifically, at the southwest corner of Commercial and Liedesdorff — where it would remain for at least another 34 years; the last directory listing for the Miners' Restaurant is in the Langley's book of 1895.

The Miners' Restaurant arrived at the middle of the 500 block of Commercial Street in 1861 just two years — perhaps less — after Joshua Norton declared himself Emperor in September 1859 only a short block to the north: at the editorial offices of the San Francisco Evening Bulletin, which were at 517 Clay, near the southeast corner of Clay and Liedesdorff Streets.

The restaurant was just a block to the east of another address famously associated with Emperor Norton. In late 1862 or early 1863 — two years, maybe less, after the Miners' Restaurant settled in at 531-533 Commercial Street — the Emperor moved in to the Eureka Lodgings at 624 Commercial, mid-block between Montgomery and Kearny, where he would live until his death in January 1880.

:: :: ::

So, for 17 years, Emperor Norton lived a one-block walk from the Miners' Restaurant. Is this the sort of place he would have frequented?

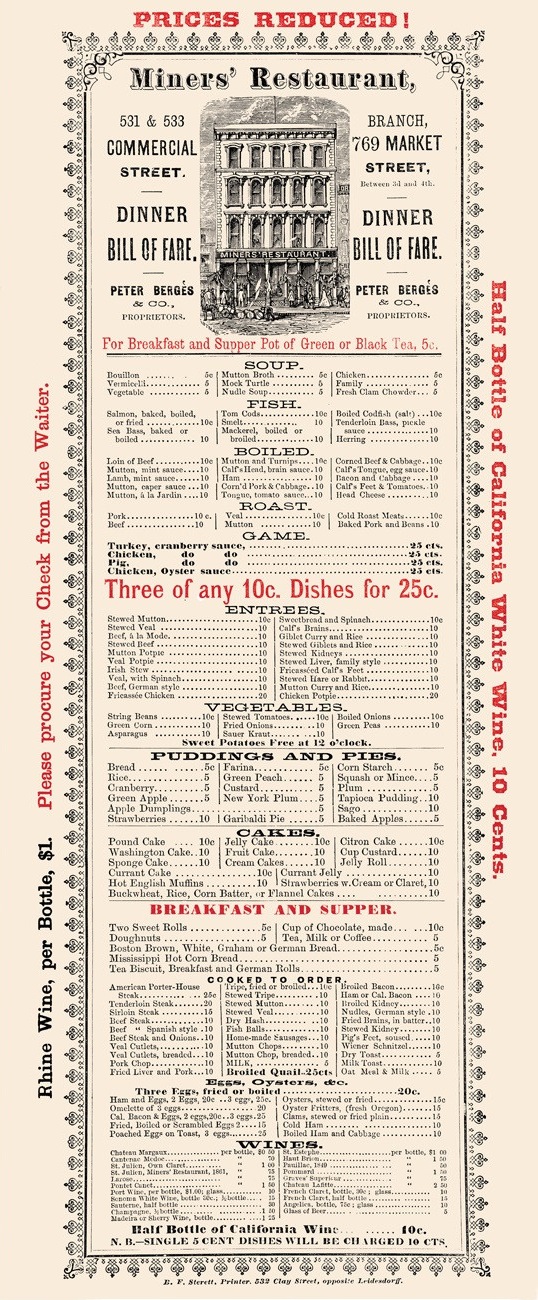

Here's a Miners' Restaurant menu from 1875:

Menu from the Miners' Restaurant, San Francisco, 1875. From the Henry Voigt Collection of American Menus. Source: Love Menu Art.

As one can see from the prices — a dime for most dishes; a nickel for some; 20 cents or a quarter for poultry, pork or a proper steak — the Miners' Restaurant basically was a diner with a decent wine list.

We know that the Emperor often took his meals at the "free" lunch counters of taverns like the Bank Exchange and Martin & Horton's, which were Montgomery Street neighbors — the Bank Exchange, in the Montgomery Block, at the southeast corner of Montgomery and Washington; Martin & Horton's, two blocks to the south, at the southeast corner of Montgomery and Clay.

In July 1875, a San Francisco contributor to Scribner's Monthly observed that, in exchange for buying a 25-cent drink at either of these two establishments, a patron could help himself to a spread of "soup, boiled salmon, roast beef, bread and butter, potatoes, tomatoes, crackers and cheese."

Almost certainly, Emperor Norton did not pay for the privilege — both because he was a teetotaler and because his very presence was good for business.

Very possibly, in the early years of the Emperor's reign, his lunch table repast was his only proper meal of the day. The Emperor's gaunt appearance in photographs of him from the 1860s would seem to bear this out.

But, by 1870 or so, Emperor Norton's fame is spreading to the rest of the country. He is starting to become a San Francisco tourist attraction. Shortly, he begins to have his own imperial promissory notes printed and to sell these to locals and visitors alike — typically, in denominations of 50 cents, but sometimes for a dollar or even for as much as five dollars or ten.

With this new source of revenue, the Emperor's straits are marginally less dire. Photographs of him from the 1870s show that he is striking a heavier — at times even portly — figure.

This leads to speculation that he was putting some of his new funds into his belly — that he was sporting himself a few extra meals a week than in his financially leaner years. (The idea that the Emperor enjoyed the freedom of San Francisco's restaurants — that he could dine where he wished at no charge — probably is just another of the many apocryphal legends that have attached themselves to him.)

Perhaps Emperor Norton added the Miners' Restaurant to his rotation.

Figure it this way: The Emperor's room at the Eureka was 50 cents a night. He would need to have sold only a couple of notes at 50 cents each to pay both for his night's bed and a filling dinner just a block from home.

:: :: ::

One person who seems to have been very familiar with the Miners' Restaurant is Mark Twain.

The restaurant comes up in Twain's 1893 story, The £1,000,000 Bank-Note. The story's narrator and protagonist, Henry Adams, and Lloyd Hastings are friends from San Francisco who are surprised to find themselves at the same dinner party in London. Hastings starts an exchange by saying:

"Dear me, it is stunning, now, isn't it? Why, it's just three months to-day since we went to the Miners' restaurant —"

"No; the What Cheer."

"Right, it was the What Cheer; went there at two in the morning, and had a chop and a coffee after a hard six hours' grind...."

The Miners' Restaurant comes up again in a reminiscence that Twain dictated on 20 December 1906 for his planned autobiography:

Six months ago, when I was recalling early days in San Francisco, I broke off at a place where I was about to tell about Captain Osborne's odd adventure at the "What Cheer," or perhaps it was at another cheap feeding-place — the "Miners' Restaurant." It was a place where one could get good food on the cheapest possible terms, and its popularity was great among the multitudes whose purses were light. It was a good place to go to observe mixed humanity.

It appears that — for a time, at least — Twain himself may have been a regular patron of the Miners' Restaurant.

Twain died in April 1910. In a feature article, "Printer Journalists in the Days of Gold," that appeared the following year in the 26 March 1911 issue of the San Francisco Call — the same paper that had provided Mark Twain with a desk next door to Emperor Norton in the summer of 1864 — Will J. French wrote:

During the winter of 1866-7 a coterie of bright journalists eked out an existence in San Francisco. Miners' restaurant was their headquarters. Charles Warren Stoddard, Bret Harte, Charles H. Webb, Prentice Mulford and Mark Twain were among the number. In 1867 Stoddard and Mulford gave public entertainments and Twain, fired with ambition, started out on a lecture tour through the smaller cities of California and Nevada. During this year — March, 1867 — he published his first book, "The Jumping Frog of Calaveras" [sic], a collection of his best fugitive sketches, and this immediately aroused public attention, not only in America, but also in England.

Based on a review of directory listings, the Miners' Restaurant was under a nearly uninterrupted succession of French owners — Corbinieu; Cordier; Drayeur; Bergès; Cazeaux; Loustaunau & Laulhere — from at least 1852 until 1890. Was it French self-respect, or was it the custom of Messrs. Twain, Hart et al. that inspired this otherwise ordinary eatery to add Chateau Lafitte to its wine list?

Whichever is the case, the success of Twain's lecture tour inspired the Daily Alta to hire him a special correspondent, with a brief to continue his travel writing from the East Coast. In the spring of 1867, Twain persuaded the Alta to pay his fare for a ship's tour of Europe and "the Holy Land." (His fifty letters "documenting" his travels and originally published in the Alta served as the basis for his second book, The Innocents Abroad, published in 1869.)

When Twain finished his tour and set foot back in New York in November 1867, he never again returned to live in San Francisco (or anywhere else in the West). So he probably was camping out at the Miners' Restaurant before Emperor Norton would have been able to afford to eat there.

But Twain's frequent visits to the 500 block of Commercial Street in 1866 and 1867 might have increased his chances of seeing the Emperor — who lived only steps away — tipping his hat and saying hello.

:: :: ::

Mark Twain's most poignant — and perhaps earliest — reference to the Miners' Restaurant comes in an episode from Roughing It (1872), his book of semi-autobiographical sketches detailing his adventures in the West from 1861 to 1867 — the period just before his 1867 tour "abroad."

He has fallen into a friendship of convenience with Blucher — name changed to protect the innocent — a newspaper man like himself, who has fallen on hard times. The episode (starting here) is worth excerpting at length:

“This mendicant Blucher — I call him that for convenience — was a splendid creature. He was full of hope, pluck and philosophy; he was well read and a man of cultured taste; he had a bright wit and was a master of satire; his kindliness and his gentle spirit made him royal in my eyes and changed his curb-stone seat to a throne and his damaged hat to a crown.

He had an adventure, once, which sticks fast in my memory as the most pleasantly grotesque that ever touched my sympathies. He had been without a penny for two months. He had shirked about obscure streets, among friendly dim lights, till the thing had become second nature to him. But at last he was driven abroad in daylight. The cause was sufficient; he had not tasted food for forty-eight hours, and he could not endure the misery of his hunger in idle hiding. he came along a back street, glowering at the loaves in bake-shop windows, and feeling that he could trade his life away for a morsel to eat. The sight of the bread doubled his hunger; but it was good to look at it, anyhow, and imagine what one might do if one only had it. Presently, in the middle of the street he saw a shining spot — looked again — did not, and could not, believe his eyes — turned away, to try them, then looked again. It was a verity — no vain, hunger-inspired delusion — it was a silver dime! He snatched it — gloated over it; doubted it — bit it — found it genuine — choked his heart down, and smothered a halleluiah. Then he looked around — saw that nobody was looking at him — threw the dime down where it was before — walked away a few steps, and approached again, pretending he did not know it was there, so that he could re-enjoy the luxury of finding it. He walked around it, viewing it from different points; then sauntered about with his hands in his pockets, looking up at the signs and now and then glancing at it and feeling the old thrill again. Finally he took it up, and went away, fondling it in his pocket. He idled in unfrequented streets, stopping in doorways and corners to take it out and look at it. By and by, he went home to his lodgings — an empty queensware hogshead — and employed himself till night trying to make up his mind what to buy with it. But it was hard to do. To get the most for it was the idea. He knew that at the Miners’ Restaurant he could get a plate of beans and a piece of bread for 10 cents; or a fish-ball and some few trifles, but they gave “no bread with one fish-ball” there.”

Would an 1870s Emperor Norton have sniffed at a dime supper of a Miners' Restaurant fish ball just because it didn't come with a slice of bread? Perhaps not if he already had enjoyed a nice literally-free lunch at the Bank Exchange.

Of course, if he'd had a good sales day, he might have afforded himself the greater selection of the menu that a spare 25 or 50 cents would have made an option.

:: :: ::

A final musing...

Those imperial metaphors — "throne" and "crown" — that Mark Twain uses to describe his "royal" friend, "Blucher": Do these foreshadow the wistful fondness that Twain showed for Emperor Norton when writing to his friend and editor William Dean Howells in September 1880, eight months after the Emperor's death?

Or are they signs of the degree to which the spirit of Emperor Norton already had seeped in to the empathetic soul of Mark Twain by the time he was writing Roughing It in 1870 and 1871?

In a letter composed on 19 and 20 October 1865 to his brother and sister-in-law, Orion and Mollie Clemens, Twain — signing "Sam" — wrote that

it is human nature to yearn to be what we were never intended for. I wanted to be a pilot or a preacher, & I was about as well calculated for either as is poor Emperor Norton for Chief Justice of the United States.

Fifteen years later, on 3 September 1880, he wrote to his friend Howells:

O, it was always a painful thing to me to see the Emperor (Norton I., of San Francisco) begging; for although nobody else believed he was an Emperor, he believed it....

What an odd thing it is, that neither Frank Soulé, nor Charlie Warren Stoddard, nor I, nor Bret Harte the Immortal Bilk, nor any other professionally literary person of S.F., has ever "written up" the Emperor Norton. Nobody has ever written him up who was able to see any but his grotesque side; but I think that with all his dirt & unsavoriness there was a pathetic side to him. Anybody who said so in print would be laughed at in S.F., doubtless, but no matter, I have seen the Emperor when his dignity was wounded; and when he was both hurt & indignant at the dishonoring of an imperial draft; & when he was full of trouble & bodings, on account of the presence of the Russian fleet, he connecting it with his refusal to ally himself with the Romanoffs by marriage, & believing these ships were come to take advantage of his entanglements with Peru & Bolivia; I have seen him in all his various moods & tenses, & there was always more room for pity than laughter.

Of course — or so it is believed — Mark Twain did "write up" the Emperor soon after his letter to Howells. Readers whose compasses point in a certain direction find Emperor Norton in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) — in the character of the King — and also see elements of the Emperor's story in Twain's earlier novel, The Prince and the Pauper (1881).

Bearing all this in mind, it seems worth noting that, in reflecting on Emperor Norton — and possibly fishing for an assignment — in his September 1880 letter to William Dean Howells, Mark Twain invoked the names of the same people who, 14 winters earlier, he was reported to have been huddling with at a "cheap feeding-place" that was within shouting distance of the Emperor's residence — a restaurant that the Emperor himself might well have started patronizing just a few years later.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...