The Secret History of One of Emperor Norton's Favorite Free-Lunch Haunts

Or, Is it Two? An 1862 Photograph Speaks from the Historical Grave

The authors of the two chief books about Emperor Norton — Allen Stanley Lane in 1939; Bill Drury in 1986 — called it Martin & Horton’s.

This was a saloon in early San Francisco that, for a time, had an especially good free-lunch counter. At the city’s better-quality saloons, like Martin & Horton’s, one could buy a 25-cent cocktail and be rewarded with one “free” pass at a lunch tabled filled with some combination of seafood, roast beef, vegetables, tomatoes, hors d’ouevres, bread and butter. Each of these saloons had its lunch-table specialties that it was known for.

In the decades after Emperor Norton’s death in 1880, those still alive who had walked the streets of the Emperor’s San Francisco — and those born a little later, who had heard the eyewitness accounts of that San Francisco from their older family members and friends — remembered and reported that Martin & Horton’s was one of the Emperor’s favorite lunch spots. Of the Emperor’s biographers, Bill Drury, in particular, shines a bright light on this saloon.

Reportedly, Emperor Norton was not a teetotaler — but, he was temperate in his drinking habits. Anecdotes vary as to whether the Emperor always had a drink with his lunch — and, if so, whether he paid for it; a friend or admirer did; or whether the saloonkeeper just waved him through, since his very presence was good for business. Probably all of the above, depending on the day.

But, it turns out that — although history remembers “Martin & Horton’s” — when Emperor Norton approached the threshold of this particular saloon, the big sign outside had a different name.

This is where our story begins.

:: :: ::

ON 18 JULY 1857, the following ad appeared in the San Francisco Daily Globe:

Clark Martin and Tom Horton were setting out on their own from Barry & Patten’s — a firm that had been in business at least since San Francisco’s fire of May 1851. Indeed, Barry & Patten’s and its free-lunch counter was one of the saloons that — together with the Bank Exchange and a handful of others — set the standard for the echelon of saloons that the new venture by Clark Martin and Tom Horton soon would join.

The new “establishment” was on the ground floor of a building at the southeast corner of Montgomery and Clay Streets — directly across Clay Street from where the Transamerica pyramid now stands. The saloon had entrances on both sides — 140 Montgomery and 153 Clay.

Langley’s city directory for 1861 showed a shift in the address numbering — the same building now being listed at 534 Montgomery and 545 Clay.

In the early-morning hours of Sunday 16 November 1862, the building was substantially gutted by a fire. The damage is documented in the following well-known photograph.

Photograph of building at the southeast corner of Montgomery and Clay Streets, San Francisco, in the wake of a fire on 16 November 1862. Historic American Buildings Survey, CAL, 38–SANFRA, 61–1. Source: Library of Congress

The building’s most high-profile tenant — and the tenant that suffered the greatest loss — was the San Francisco Daily Morning Call newspaper.

It’s remarkable how many different enterprises there were in this not-particularly-large building. According to the next-day account in the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin, the Morning Call and Martin & Horton’s shared the building with:

a cigar store, Leony & Hirstel;

an oyster saloon, Quinlan’s;

a barber shop run by Antonio Flercs;

Fish & Co, an employment office; and

in the cellar, a lager beer saloon owned by “F. Hug.”

The fire is what prompted the Morning Call to move to 612 Commercial Street, between Montgomery and Kearny, in 1863 — within a year or two of when Emperor Norton moved next door to 624 Commercial. The Call still was at 612 when Samuel Clemens, the future Mark Twain, moved to San Francisco to take a desk at the Call in summer 1864.

The photograph shows men teeming in and out of both sides of Martin & Horton’s place. Indeed, according to the Daily Alta California newspaper’s report of 19 November 1862 — just three days after the fire — Martin & Horton’s didn’t miss a beat:

Item on quick recovery of Martin & Horton’s saloon and the Faust Cellar following a a fire in their building at the southeast corner of Montgomery and Clay Streets, Daily Alta California, 19 November 1862, p. 1. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

What was “the Faust Saloon”? This wasn’t listed in the roster of businesses the Bulletin published with its 17 November 1862 report of the fire.

As if to correct the Bulletin, the Alta in its own November 17th account of the fire referenced “[t]he Faust Lager Beer Saloon, owned by Joseph Hug, in the cellar directly under the cigar shop.”

The following detail from the post-fire photograph shows a sign, center right, that carries the proper name of the place: Faust Cellar.

Detail from photograph of building at the southeast corner of Montgomery and Clay Streets, San Francisco, in the wake of a fire on 16 November 1862. The sign for the Faust Cellar saloon is visible at center right. Historic American Buildings Survey, CAL, 38–SANFRA, 61–1. Source: Library of Congress

:: :: ::

LeCount & Strong’s San Francisco directory of 1854 lists Joseph Hug as having a “lager bier house” in the basement of a building at the corner — presumably the southeast corner — of Montgomery and Clay.

The following photograph of the building — the same building shown in the 1862 photograph above — is dated c.1854–55, a couple of years before Martin & Horton’s arrived.

Photograph of building at the southeast corner of Montgomery and Clay Streets, San Francisco, c.1854–55. Attributed to George H. Johnson (1823–1879), proprietor of Johnson’s Daguerrean Rooms, shown in the photo. Collection of the Nelson–Atkins Museum of Art. Source: California Sun

Click to enlarge, and you’’ll see that the Faust Cellar sign already is there. Although it’s faint, the sign appears to read “Faust Cellar” at the top — just with different typography that had been repainted by 1862. And, along the bottom of the sign — below the word “BY” — appears to be the name “Hug” at bottom right.

Also of note: This earlier photo shows an external staircase providing direct access to the “Cellar” from the sidewalk. It’s not clear from the 1862 photo whether that staircase still is in place.

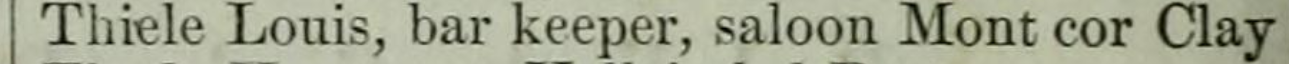

The 1856 city directory by Harris, Bogardus & Labatt lists a Louis Thiele as a barkeep at a saloon at the corner of Montgomery and Clay.

Langley’s 1860 directory lists Joseph Hug as still having his “liquor saloon” at the southeast corner of Clay and Montgomery. But, Thiele now is listed as being a barkeeper “with Joseph Hug” — suggesting that he might have taken a stake in the business.

Langley’s 1861 listing for Hug includes what may be the first reference to the saloon as “Faust Cellar.”

At least by this time, Louis Thiele was going by “George.”

Expanding on this, an item in the Daily Alta of 15 November 1862 — the day before the fire at the southeast corner of Montgomery and Clay — notes that Joseph Hug won a share of a lottery ticket as a prize in a sharpshooting contest and gave a quarter of his share to “Mr. Louis Thiele, better known as ‘George,’ at the Faust Cellar.”

Item describing Louis Thiele as being “at the Faust Cellar” and noting that he was “better known as ‘George,’” Daily Alta California, 15 November 1862, p. 1. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Later accounts portray “George” as something of a genial raconteur. The fact that Hug is not associated with the Faust Cellar in this item suggests that — whatever his ownership stake — George may have emerged as the front man of the saloon.

Joseph Hug is last listed at the Faust Cellar in the directory of 1864; the 1865 directory shows him in real estate.

On 11 August 1865, the Daily Alta ran the following ad indicating that the Faust Cellar now was A.L. “George” Thiele’s place and detailing the shape of things to come.

Ad announcing renovation and expansion of the Faust Cellar and identifying Louis Thiele as the proprietor, Daily Alta California, 11 August 1865, p.2. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Soon, Thiele adopted a regular ad that looked like this:

By summer 1866, the Faust Cellar was known as a place where, according to the following San Francisco Chronicle item, “[e]very night, between the hours of 9 and 12, the leading Bohemians of the San Francisco daily and weekly Press can be seen…discussing the topics of the day over their lager and caviare.”

An ad that began appearing in early 1869 — promoting “Sandwiches of All Kinds” — suggests that Thiele might have wanted to make sure the public knew that his place wasn’t as hoity-toity as all that:

An ad that ran on 13 August 1869 showed Thiele with a new business partner: “W. Sievers.”

It appears that the last “Thiele & Sievers” ad for the Faust Cellar ran in late September 1869. Then, after four months of silence, a notice that appeared in the Daily Alta of 4 February 1870 — Emperor Norton’s 52nd birthday — announced that “George” had “sold out his interest” in the Faust Cellar and — the next day — would be opening a new spot, called “George’s,” at the southwest corner of Bush and Montgomery Streets.

It’s reasonable to guess that Thiele sold his interest to Sievers. But, even if so: Was Sievers the only other owner? Might Clark Martin and Tom Horton — individually, or as the business entity of “Martin & Horton’s” — been silent partners in the Faust Cellar, and did they now have a greater stake? It’s reasonable to wonder.

Ad announcing that “George” Thiele had sold his interest in the Faust Cellar and was opening a new spot further south on Montgomery Street, to be called “George’s,” Daily Alta California, 4 February 1870, p.2. Source: California Daily Newspaper Collection

:: :: ::

A NOTICE FOR THE DEMOLITION of the Martin & Horton building appeared in March 1873:

A month later, the following notice for the auction of the building:

So, what happened to Martin & Horton’s?

A few days after the auction notice, the following appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle — notice of a “change of base” to 111 Liedesdorff Street.

It’s not clear whether the Leidesdorff location was a saloon or just an address where Martin and Horton continued their wholesale business. During this period, there don’t appear to be any newspaper ads for a saloon at this address. But, this might not tell us much, given that Martin & Horton had run very few ads for their saloon at Clay and Montgomery.

In August 1874, there was a notice for a 3-year lease for the Faust Cellar space.

It’s hard to know what to make of this. On the one hand, the timing suggests that a replacement building was…in place. On the other hand, any “place known as the Faust Cellar” would have been lost in a demolition of the building where the Faust Cellar was.

This much is clear: It appears that there were no ads for the Faust Cellar from September 1869 until December 1873. When ads returned, they were published only in German-language publications until April 1874, with notices picking up again in this vein in August–November 1876 and the last trace appearing a couple of years later.

The glory days of the Faust Cellar ended with the departure of “George” Thiele in late 1869.

In August 1875, there was a notice for another 3-year lease in the Martin & Horton building — this time, for a cigar store.

Langley’s 1875 directory for San Francisco showed Martin & Horton’s in the same building, with the 545 Clay address that they’d been using since 1861.

What’s interesting is that the Martin & Horton’s listings in the 1873 and 1874 directories used the same address — notwithstanding the firm’s 1873 announcement of a “change of base” to 111 Leidesdorff. This could be a sign that Clark Martin and Tom Horton expected their dislocation from the southeast corner of Montgomery and Clay to be brief, and that they wished to preserve their association with that location. Or it could mean that the auction and demolition of the building where they and the Faust Cellar had been doing business for nearly 20 years never came to pass.

It seems worth noting that the March 1873 demolition notice reported J.L. Riddle as an owner of the building — and that, in August 1875, Riddle was listed as the lessor of the cigar store on the same corner.

:: :: ::

ON 31 AUGUST 1884 — a little more than four-and-a-half years after the death of Emperor Norton, the San Francisco Examiner ran the following item documenting that Martin & Horton’s still was in business at the corner of Montgomery and Clay:

Seventh months later, in March 1885, came the following auction notice for the building. The description of the building as “brick” confirms that, indeed, the original building — which was wood — was demolished and replaced in 1873–74.

Notice for auction of Martin & Horton building, Daily Alta California, 30 March 1885, p. 3. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

A little more than two years after this, in June 1887, Tom Horton was ready to call it a day.

Notice of Tom Horton’s retirement from Martin & Horton’s and sale of his half-interest in the firm, Daily Alta California, 29 June 1887, p. 2. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Indeed, the San Francisco directory of 1887 would feature the final listing for Martin & Horton’s.

:: :: ::

IN HIS 1986 BIOGRAPHY of Emperor Norton, William Drury makes much of the reputation of Martin & Horton’s as a favorite of newspapermen — and of the stories that the Emperor too frequented this saloon, drawn by its clientele and its “free lunch” counter.

The basic discovery documented above is that there were two locally famous eating-and-drinking establishments in the building at the southeast corner of Montgomery and Clay Streets — not just one — and that both spots were hangouts for journalists and writers.

Which begs a question: Was Emperor Norton seen only at Martin & Horton’s? Or, once inside the building, did he sometimes venture downstairs to the Faust Cellar as well?

Or, in fact: Was the Faust Cellar the Emperor’s real destination?

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...