Emperor Norton Does Art Criticism With a Borrowed Jackknife — And the Crowd Loves It

The Best-Documented Instance of the Emperor’s Royal Displeasure Over How He Was Visually Portrayed

FRIENDS, ASSOCIATES and observers of Emperor Norton noted that, in private and in public, he generally was a sober, gentle, and reasonable presence, except — except when anyone questioned or challenged his root claim that he was, in fact, the Emperor. In such cases, he could become quite angry.

Corollary to this was the Emperor’s view about how he should be portrayed in art, photography, and theater. He did not want to be cast in a humorous or mocking light.

This must have been hard for the Emperor, who was a figure of burlesque and artistic caricature almost from the beginning:

In September 1861, two years after Emperor Norton staked his imperial claim in September 1859, a two-act musical burlesque, Norton the First, or, Emperor for a Day, opened at the year-and-a-half-old Tucker Hall, on Montgomery Street between Pine and California.

As early as 1861, Edward Jump’s cartoons lampooning the Emperor began to circulate in San Francisco.

By the mid 1860s, Emperor Norton began to be seen as a stock character at masquerade balls around the city and elsewhere in Northern California.

Perhaps the most oft-cited example of Emperor’s Norton’s royal indignation over being made the butt of an artistic joke took place in 1863, when the Daily Alta newspaper reported that the Emperor tried to smash the window of a shop where a sketch of him was being displayed.

“Vive L’Empereur,” item on Emperor Norton’s confrontation with a shop window where a sketch of him was being displayed, Daily Alta California, 14 February 1863, p. 1. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

The Alta doesn’t provide any details about the sketch that elicited the Emperor’s ire. But, the date of the item coincides with the date often cited for Edward Jump’s cartoon, “The Three Bummers,” which shows Emperor Norton at a free-lunch table with the dogs Bummer and Lazarus — leading some to conclude that this may have been what was behind the window that the Emperor was trying to smash.

"The Three Bummers," around February 1863, by Edward Jump (1832–1883). Collection of the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. Source: KQED

Six years later, in March 1869, Emperor Norton posed for Eadweard Muybridge’s well-known photograph of him astride a boneshaker:

Emperor Norton, early March 1869. Photograph by Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904). Taken in front of the fourth Mechanics' Pavilion, at the northwest corner of Stockton and Geary Streets, San Francisco, during a “velocipedestrian training school” that was held at Pavilion starting in early February 1869. Collection of the Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley. Source: Calisphere

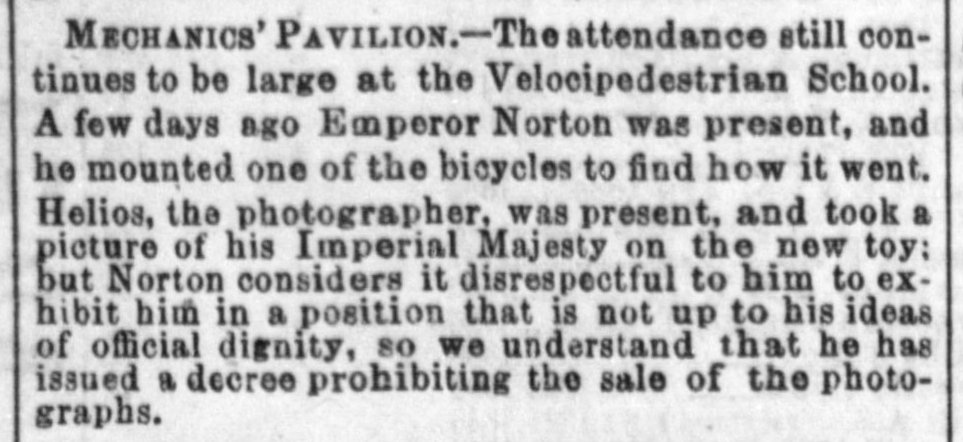

An item about the photograph that appeared in the Alta a few days later suggests that the Emperor might have regretted his decision to allow himself to be photographed in this posture:

Item on Eadweard Muybridge’s photograph of Emperor Norton on a boneshaker, Daily Alta California, 8 March 1869, p. 1. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

:: :: ::

RECENTLY, I uncovered a vivid later instance of Emperor Norton’s being lampooned in art — and of his own demonstration in protest — that is much better documented than the familiar examples above.

By 1875, the new Safe Deposit Building was standing at the southeast corner of Montgomery and California Streets, San Francisco:

Stereocard of Safe Deposit Building, southeast corner of Montgomery and California Streets, San Francisco, 1875. Photography by Carleton Watkins (1829–1916). Collection of the California State Library. Source: Calisphere

But, in the fall of 1874, this building still was under construction — and the construction site was enclosed by a temporary wooden fence.

This fence was a magnet for advertisements and what we might now call “guerilla art.”

So it was that an enterprising business put up a large-scale ad on the fence that used a depiction of Emperor Norton to attract eyeballs. As this item from the Daily Evening Bulletin of 3 September 1874 makes clear, the Emperor didn’t like it:

Borrowing a jack-knife from a bystander the Emperor in person rent the offensive caricature into shreds, amid the plaudits of a large crowd who witnessed the royal indignation.

The next day, September 4th, the San Francisco Chronicle covered the incident this way:

The Emperor borrowed a jackknife of Major Smiley on yesterday morning and cut it out, leaving the fragments of the canvas flapping in the wind, as a warning to triflers with the royal dignity.

The Emperor’s September 1874 protest at Montgomery at California Streets made enough of an impression that it was remembered 7 months later — and in greater detail — in this letter that appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle of 7 April 1875.

In the afternoon His Majesty the Emperor, incensed at the comparison between himself and Michael Reese, deliberately cut the canvas (13 x 18 feet) from the pine frame, and, taking his likeness out, sliced it into strips in the presence of an applauding populace.

Michael Reese (1817–1878) was a wealthy San Francisco capitalist and real estate developer who was an early benefactor in the establishment of the University of California, and who, at his death, left the University some $750,000 and other charitable institutions — including hospitals and orphanages — bequests totaling upwards of $500,000.

But, Reese was known primarily as a surly, self-righteous, acquisitive, greedy miser.

By the mid 1860s, journalists, humorists, and cartoonists could be found trolling for laughs by creating satirical associations between Michael Reese and the Emperor Norton.

In fact: Before George Frederick Keller (1846–1927) became the staff artist for the San Francisco Illustrated Wasp, where he caricatured the Emperor numerous times, he created the following cartoon that appeared in a different publication:

This triptych originally was published in the weekly Thistleton’s Jolly Giant — and, strong evidence suggests that the date of publication was sometime in 1873 or early 1874.

So, it’s entirely possible that this was the artwork used in the fence-mounted advertisement that Emperor Norton “knifed” in September 1874.

What’s remarkable is that, having endured this kind of public humor at his expense for more than a decade, the Emperor was not inured to — or immune to being wounded by — it. He was capable of being drawn to the same level of righteous offense and anger in 1874 as when he hammered the store window in 1863.

Arguably, this could be seen as a sign of the sincerity of his belief and the authenticity of his cause.

One almost can imagine the Emperor seeing his image on the street ad and thinking to himself: “I’ve been at this for 15 years. Don’t they realize yet that I’m perfectly serious?

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...